The Jewish Question

Whizzing through an intersection of Phnom Penh in a tuk-tuk early Saturday morning, a man, frantically waving a shawl in the air, shouted to me. What he said was indistinct however, the urgency in his voice was unmistakable. I suggested we go back and see if he required assistance. The driver executed a tight turn and hastened back. The man, relieved, breathlessly asked, “Are you a Jew?”

Whizzing through an intersection of Phnom Penh in a tuk-tuk early Saturday morning, a man, frantically waving a shawl in the air, shouted to me. What he said was indistinct however, the urgency in his voice was unmistakable. I suggested we go back and see if he required assistance. The driver executed a tight turn and hastened back. The man, relieved, breathlessly asked, “Are you a Jew?”

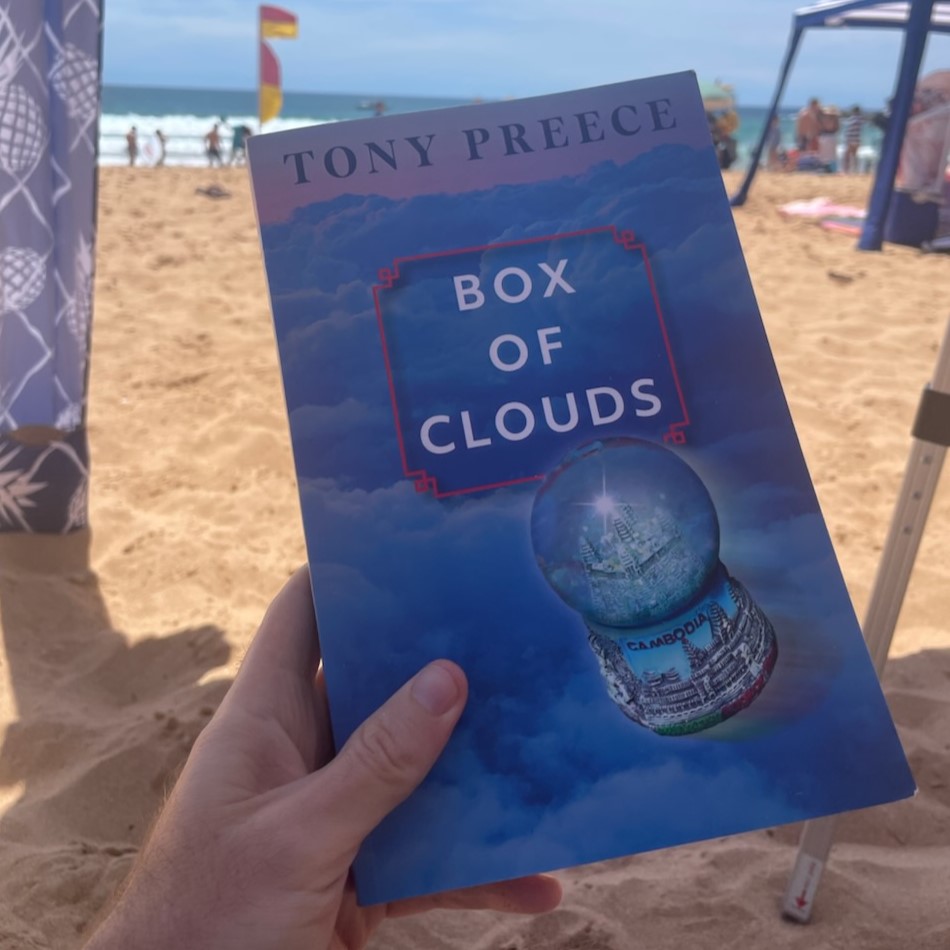

Confidentially, I’ve harboured secret suspicions since my lonely teens growing up in a remote country town. All it took was reading Mila 18 then Exodus in quick succession. I knew instantly I was an orphaned Jewish boy, adopted by these well-meaning people I had nothing in common with, yet had come to know as, “my parents”. To be spotted as a Jew, by my own kind, in a speeding vehicle, at 8:30am, in a broken dusty back street, forty-nine years later was obviously some high form of vindication. Here in Cambodia for one moment my star shone brightly, albeit briefly, before declining my people’s call.

Proceedings had stalled at Chabad Jewish Centre. He urgently needed one more man to form a quorum for morning prayer. I offered but said if they ran a physical to check my bona fides I would be overqualified. This would not be the first time I was rejected by the Jews.

As an earnest, young man from the country, naive to Melbourne city ways, I rented a sparse flat in Balaclava. A former racing swimmer of sorts I sought to join a club and compete again. The local newspaper ran an article inviting people to join the nearby Hakoah Club in Inkerman Street. Speedos and goggles in hand I answered the call. It took three weeks, many quizzical side-long glances and sniggering in the change room for it to dawn on me why they wouldn’t socialise after sundown on Friday, or race on Saturdays. Circumcision? Well that’s no skin off my nose.

This obsession had to find resolution. With that foremost in mind, curiosity led me through France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, and Poland. Being on the ground in the Jewish quarters raised as many questions as provided answers. To walk in memory of the victims of Hitler’s despicable final solution; the streets, footsteps echoing in cobblestoned lanes, listen to the sounds, feel the weight of silence, faded images and remnants of the Star of David, stand amid the remaining artifacts of lives extinguished, the abomination of death camps, feel overwhelming guilt when faced with people’s lives made museum exhibits, showcases of everyday common use utensils, hear ghostly voices from the past, gaze into faces frozen in black and white, solemnity of synagogues, the articles of religion that branded Jews pariah.

This obsession had to find resolution. With that foremost in mind, curiosity led me through France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, and Poland. Being on the ground in the Jewish quarters raised as many questions as provided answers. To walk in memory of the victims of Hitler’s despicable final solution; the streets, footsteps echoing in cobblestoned lanes, listen to the sounds, feel the weight of silence, faded images and remnants of the Star of David, stand amid the remaining artifacts of lives extinguished, the abomination of death camps, feel overwhelming guilt when faced with people’s lives made museum exhibits, showcases of everyday common use utensils, hear ghostly voices from the past, gaze into faces frozen in black and white, solemnity of synagogues, the articles of religion that branded Jews pariah.

Standing in Poland’s Warsaw ghetto, setting for the novel Mila 18, it is time to leave fiction and face reality. In 1940 Jewish residents of Warsaw were commanded to move into the designated area, sealed off, and enclosed by a wall over 10 feet high, topped with barbed wire, over 400,000 Jews were contained in an area of two square kilometres, with an average of 7.2 persons per room. The ghetto was closely guarded to prevent movement between the rest of Warsaw.

On April 19, 1943, Himmler’s SS forces entered with tanks and heavy artillery to liquidate the ghetto. Several hundred resistance fighters armed with a small cache of weapons fought the Germans for nearly a month. Block by block buildings were systematically razed, destroying bunkers where residents were hiding. In the process, thousands of Jews were killed or captured. By May 16, the ghetto was firmly under Nazi control, and in a final symbolic act blew up Warsaw’s Great Synagogue. An estimated 7,000 Jews perished during this uprising, nearly 50,000 survivors were sent to extermination or labour camps.

Now it is re-built, an impeccable replica includes the Old Town Market, townhouses, the circuit of the city walls, the Royal Castle, and important religious buildings. Today the sun shines off brightly painted walls, glistens off casement windows. Even the central fountain decoratively sprays water. There is music and pockets of laughter, business is being done. Without this Warsaw would not have a tourist trade. And where once the lower floors would have bustled with Jewish trade the bevelled brick facades house gifts shops, cafes, and ice-creameries.

My last destination sits further south, outside Krakow, six hours by bus, 313 kilometres away, Auschwitz and Birkenau. The cruelest lie stands above the main gate entering Auschwitz; an inscription reads “ARBEIT MACHT FREI” (work makes you free). Auschwitz was a concentration camp to punish and exterminate opponents of the Nazi regime. Nearby, Birkenau operated for the specific purpose of making Europe ”Judenrein” (free of Jews). Hitler’s answer to the Jewish question. The final solution took the lives of 90% of the Polish-Jewish population, two-thirds of the European Jewry. Around six million in total.

My last destination sits further south, outside Krakow, six hours by bus, 313 kilometres away, Auschwitz and Birkenau. The cruelest lie stands above the main gate entering Auschwitz; an inscription reads “ARBEIT MACHT FREI” (work makes you free). Auschwitz was a concentration camp to punish and exterminate opponents of the Nazi regime. Nearby, Birkenau operated for the specific purpose of making Europe ”Judenrein” (free of Jews). Hitler’s answer to the Jewish question. The final solution took the lives of 90% of the Polish-Jewish population, two-thirds of the European Jewry. Around six million in total.

So complete was the design for annihilation a system of symbols signified each person’s incarceration by coloured patches sewn onto their striped prison uniform. Almost universally recognised is the yellow star (Jew), perhaps less well known is the inverted pink triangle (homosexual). Criminals were marked with green inverted triangles, political prisoners with red, “asocials” (including Roma gypsies, nonconformists, vagrants, and other groups) with black or in some camps brown triangles, Jehovah’s Witnesses with purple. Non-German prisoners were identified by the first letter of the German name for their home country, which was sewn onto their badge. The two triangles forming the Jewish star badge would both be yellow unless the Jewish prisoner was included in one of the other prisoner categories. A Jewish political prisoner, for example, would be identified with a yellow triangle beneath a red triangle.

Auschwitz is now a museum. Accompanied by a guide offering continuous narration, small groups move through the building at quite a clip. Exhibit after exhibit there is little time for reflection or sentiment as you are led through a warren of corridors and rooms, upstairs and down, into basements expressly used for solitary confinement and torture, across courtyards still bearing pockmarks from volleys of bullets by firing squads. Even a walk into thick cement underground death chambers complete with overhead showers that dispensed gas. Finally, the ovens.

Auschwitz is now a museum. Accompanied by a guide offering continuous narration, small groups move through the building at quite a clip. Exhibit after exhibit there is little time for reflection or sentiment as you are led through a warren of corridors and rooms, upstairs and down, into basements expressly used for solitary confinement and torture, across courtyards still bearing pockmarks from volleys of bullets by firing squads. Even a walk into thick cement underground death chambers complete with overhead showers that dispensed gas. Finally, the ovens.

Coming into view, train tracks disappearing into the long low red brick facade is unmistakably Birkenau. This image, seen countless times in photos, movies, historical documentaries, typifies the Holocaust and strikes dread into the hearts of all who enter. The camp is stark, the Nazis having destroyed as much of the camp infrastructure as possible upon realising time was up. What is extant paints a picture of unbearable sorrow. The scope of mass murder across Europe, the detail so complex, attempting to do justice to the millions of lives taken would be lost here. Those with a conscience seeking knowledge and wisdom, those who have a genealogical link will spend years pursuing their truth. Wrestling with the physical evidence of genocide becomes difficult to know how to manage the flood of emotion. And that should be the reaction at the very least. For me came a whisper from early childhood, before the man in the street in Phnom Penh, before the Hakoah Swimming Club, even before Mila 18.

I went to Sydney on my own as an eleven-year-old in 1961. Part of a Young Australia League excursion for one week. I joined the group in Melbourne, the lone boy from the bush. A bus to Sydney where hundreds of boys were housed at the Showgrounds in large pavilions. Rows of canvas camp stretchers, a ticking mattress, a sheet, and blanket would be home. We fell asleep to snoring, farting, burping, laughing, whispered prayers, screaming nightmares, and crying. Lonely boys gathered from around Australia. Each morning we were herded onto buses and driven to points of interest, the city and Botanic Gardens, The Gap and Bondi Beach, Taronga Park Zoo, Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, Circular Quay, and a ferry across the harbour to Manly Beach. Stuart was also on his own, we shared a bus seat. The second day I was spat on, pushed, and shoved, and hounded by the call “Jew lover.” Confused and hurt I had no understanding what was meant but the tone left no doubt it was not nice. My travel friend taunted with the chant “Stu the Jew” explained as best he could. It lasted only a week for me, but for Stuart it was daily.

Educate. You get your answer when you learn the truth. I am not Jewish. Holocaust denial is ignorant, and dangerous. Bigotry is acquired. Hatred is learned.