Beauty Under Glass

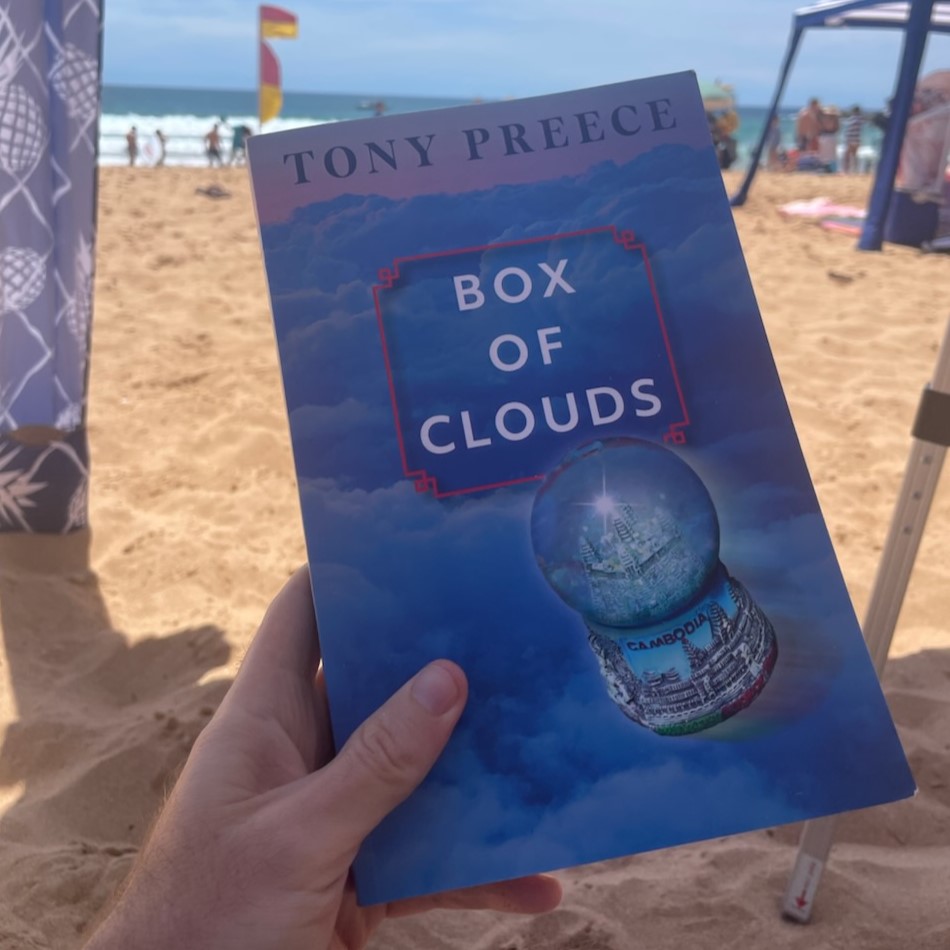

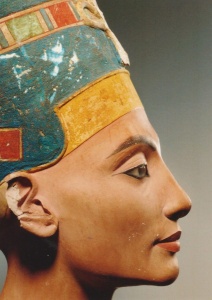

Through the swirling snowflakes a wan female face peers. Captured inside the glass dome is the world’s most beautiful woman, Queen Nefertiti, wife of Pharoah Akhenaton who ruled Egypt between approximately 1370 and 1333 BC. Feeding the fantasy of Egyptology this little tourist treasure remains a best seller the length and breadth of the Nile River from Alexandria to Aswan. The variants advanced over time and technology have not dimmed her allure.

Through the swirling snowflakes a wan female face peers. Captured inside the glass dome is the world’s most beautiful woman, Queen Nefertiti, wife of Pharoah Akhenaton who ruled Egypt between approximately 1370 and 1333 BC. Feeding the fantasy of Egyptology this little tourist treasure remains a best seller the length and breadth of the Nile River from Alexandria to Aswan. The variants advanced over time and technology have not dimmed her allure.

Her beauty is not confined to snow globes, freestanding miniatures to full sized, and extra OS replicas, unadorned to outlandishly gaudy, all tastes catered for. If that is not your style there are still T-towels, dinner mats, drink coasters, papyrus wall hangings, and an unimaginable range of T-shirt designs. Brandishing their piece of take-away Egypt, stall holders and touts engage tourists in the game of haggling and will chase you into the Sahara Desert, around ancient archaeological sites, through narrow overcrowded laneways, up and down rugged outcrops, over rubble strewn carparks in the blazing heat of day, into the dead chill of night. This is a game played every day, and you will not leave empty handed.

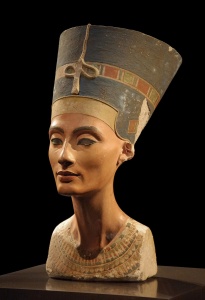

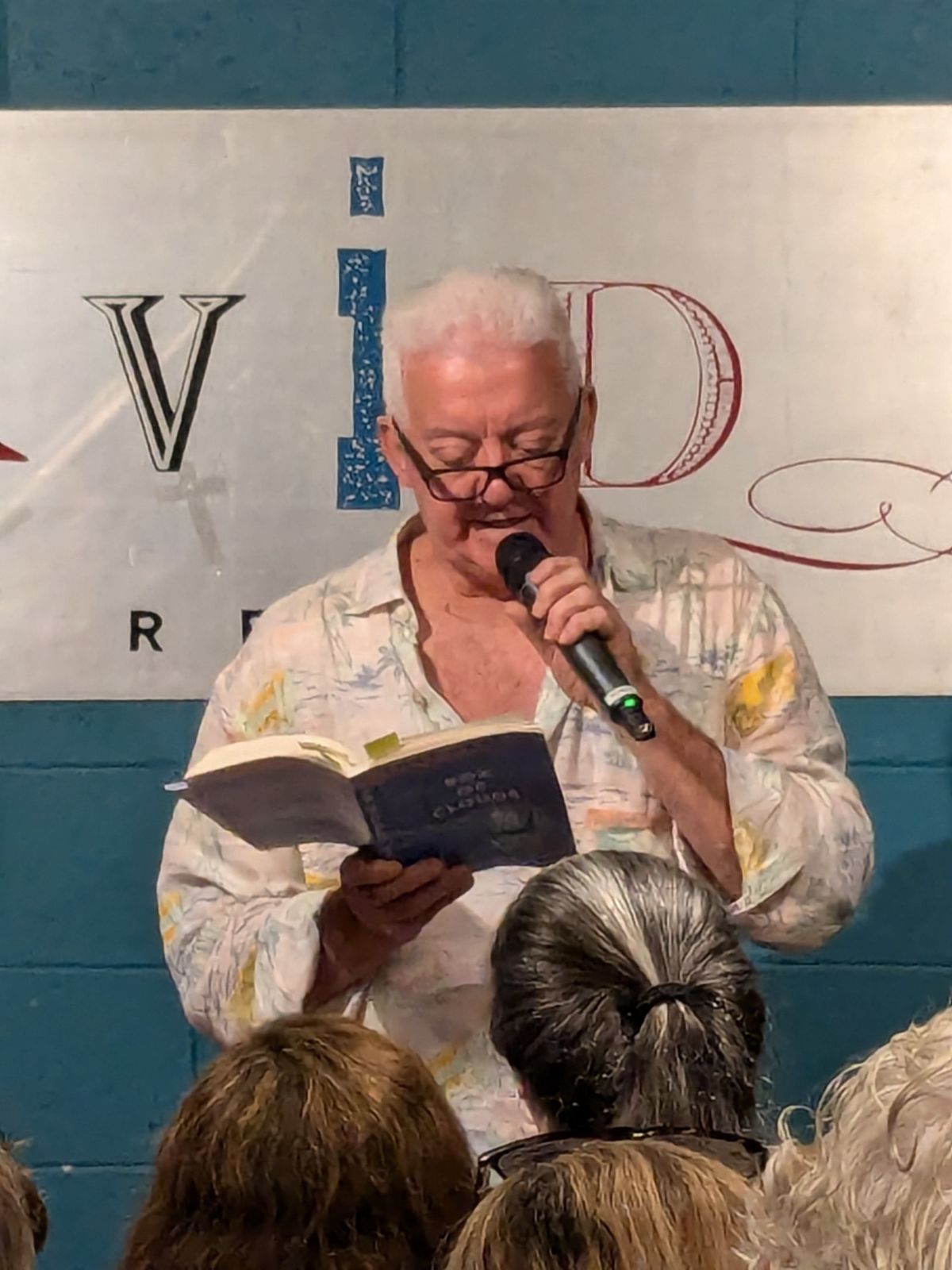

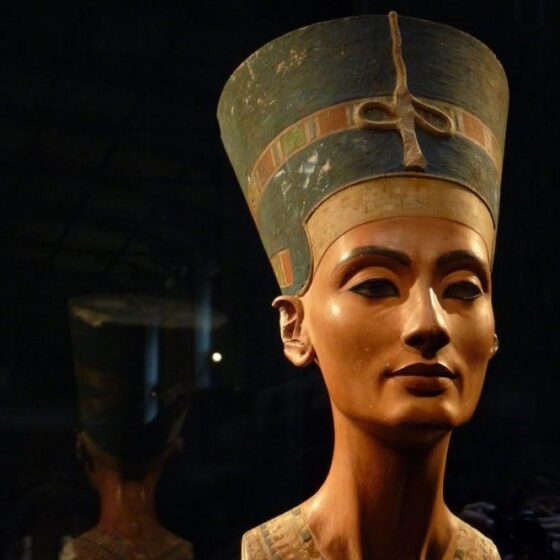

Spare a thought now for the original Nefertiti. Did you know she lives in Berlin? The sole occupant in a salubrious architect designed room, and like her bottled facsimile caged under glass. Albeit in a larger case hermetically sealed for her own preservation. Sat on a pedestal positioned slightly above eye level viewers gaze up at her, 48 cm (19 inches) tall, weighing 20 kg (44 lbs). Home to Nefertiti is Neues Museum, one in the cluster of five on Museum Island in Central Berlin. The journey to what is largely accepted to be her last resting place has been arduous.

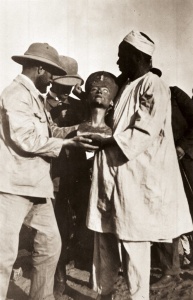

Hauled from the Sahara’s shifting sands at Tell el-Armana near Cairo on 6 December 1912 during a German excavation campaign led by Egyptologist and architectural historian Ludwig Borchardt and scurrilously shipped to Berlin in 1913 she was presented to a wholesale cotton merchant, the sponsor of the excavation. James Simon, the recipient, had her on display in his home until lending her to the Berlin Museum. She became a permanent acquisition in 1920 but kept under wraps until 1924. Presented to the world Nefertiti created a sensation becoming an icon of feminine beauty, a universally recognised artifact from Ancient Egypt. The onset of World War II in 1939 closed the museum. Moved to shelter for safekeeping Nefertiti was once more plunged into a dark underground world.

Hauled from the Sahara’s shifting sands at Tell el-Armana near Cairo on 6 December 1912 during a German excavation campaign led by Egyptologist and architectural historian Ludwig Borchardt and scurrilously shipped to Berlin in 1913 she was presented to a wholesale cotton merchant, the sponsor of the excavation. James Simon, the recipient, had her on display in his home until lending her to the Berlin Museum. She became a permanent acquisition in 1920 but kept under wraps until 1924. Presented to the world Nefertiti created a sensation becoming an icon of feminine beauty, a universally recognised artifact from Ancient Egypt. The onset of World War II in 1939 closed the museum. Moved to shelter for safekeeping Nefertiti was once more plunged into a dark underground world.

It would be another six years of shuffling locations before she was to reclaim her position as the most famous bust of ancient art, comparable only to the mask of Tutankhamun. She was brought back to light post war in March 1945 by the American Army, and handed over to its Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives branch. After the brutalities of a long war having escaped Berlin, survived burial in the salt mines, rattled up the bombed-out roads to Frankfurt and endured seclusion in the vaults of the Reichsbank, the crate containing Queen Nefertiti rolled onto the Rhine River docks at Wiesbaden. Workers pried open her crate, peeled off a protective inner wrapping of tarpaper to come to a thick cushioning layer of white spun glass. “The Painted Queen is here,” a worker cried. “She’s safe!” But not yet home.

The abridged trip home reads: on public display in Wiesbaden in 1946 before transferred in 1956 to a museum in West Berlin (the city still divided East/West by the wall). In 1967 the bust is moved to the Egyptian Museum in a borough of Berlin and remained until 2005. She returns to the Neues Museum as its centrepiece when the museum reopened in October 2009. Queen Nefertiti living up to the translation of her name “the beautiful one has come forth.”

Her public debut in 1924 was auspicious. Capturing imagination, she rapidly impinged on the consciousness of the western world who grappled to describe her rarity. More than allure and charisma, she personifies and embodies hauteur. Helen of Troy’s face may well have launched a thousand ships, but Nefertiti with only one eye and a badly chipped right ear spawned a billion-dollar beauty industry. An Egyptian proverb goes, ‘a beautiful thing is never perfect.’

Her chequered history has served to raise her profile, enhance the mythology, enshrine her iconic stature, raise the enchantment levels, commanding attention, captivating an adoring global public. It was not long, and not unexpected, until her image was objectified, commodified, and entered popular culture.

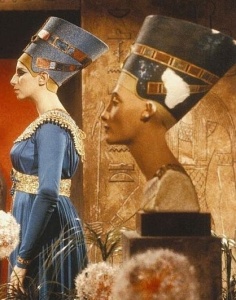

In 1935 the American science fiction horror film Bride of Frankenstein borrowed heavily for the distinctive look designed by Jack Pierce, played with startling effect by Elsa Lanchester. Showbusiness phenomenon and ugly duckling, Barbra Streisand appropriated Nefertiti’s image for the 1966 television special and album release, Color Me Barbra. In 1989 a 70-pfennig stamp featured the bust of Nefertiti on issue in Germany. Iman embodies her in the 1992 Michael Jackson video clip Remember the Time. Her bust appeared in 1999 on an election poster for the German green political party as a promise for a cosmopolitan and multi-cultural environment with the slogan “Strong Women for Berlin!”

Every make-up maven’s wildest dreams were answered as Helena Rubenstein, Revlon, Max Factor, Elizabeth Arden were early starters in products specifically aimed at achieving the Egyptian look. Fashion evolves, over time favourite trends peak, then disappear, only to return for a second, fourth, tenth season. The death of Amy Winehouse in 2011 took her heavily mascaraed Egyptian influenced eye make-up look with her. Yves Saint Laurent put it best when he said, “The most beautiful make-up of a woman is passion. But cosmetics are easier to buy.”

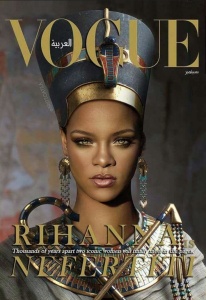

By 2015 Algerian model Farida Khelfa spectacularly covered Nefertiti for Christian Louboutin Beauty, photographed by Ali Mahdavi. No denying Rihanna’s commitment to Nefertiti evidence is worn as a rib tattoo. However, her 2017 Vogue Arabia cover was not met well, rounded on for cultural appropriation. One Twitter user stated: Ok sorry but Rihanna is NOT Egyptian girl you’re a queen yes, but take that crown off.

And so, we return to Berlin where the cult of Nefertiti began. Through the intervening years controversy has followed. Doubts cast as to the authenticity of the bust dogged but never dulled her. Carbon dating and extensive 3D imaging silenced the rumour mongers putting them out of business. Calls for her to be returned to her country of origin persist. Egypt’s claim she was stolen and spirited out of the country by the German excavation team are at the heart of the matter.

And so, we return to Berlin where the cult of Nefertiti began. Through the intervening years controversy has followed. Doubts cast as to the authenticity of the bust dogged but never dulled her. Carbon dating and extensive 3D imaging silenced the rumour mongers putting them out of business. Calls for her to be returned to her country of origin persist. Egypt’s claim she was stolen and spirited out of the country by the German excavation team are at the heart of the matter.

Remember James Simon, the Berlin cotton merchant she was gifted too? As a dying wish he requested she be repatriated but was refused. Egypt’s deposed Prime Minister Hosni Mubarak drove the final nail into the debates coffin. He stated she could stay in Berlin as she did more for Egypt’s tourism industry than advertising could ever achieve. The bust is still “a Berlin woman”, as the author Dietmar Strauch calls Nefertiti in his book published in 2017, “James Simon: The Man who Made Nefertiti a Berliner.”