Dickens of a Time

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. It was the dickens of a time locating 48-49 Doughty Street, Holborn, in the London Borough of Camden. The goal today, find a typical Georgian terraced house which was Charles Dickens’s home from 25 March 1837 to December 1839. It seems so straightforward on the map. With rain threatening the sky is overcast, a sludgy grey, yet nothing will cast a pall over this day.

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. It was the dickens of a time locating 48-49 Doughty Street, Holborn, in the London Borough of Camden. The goal today, find a typical Georgian terraced house which was Charles Dickens’s home from 25 March 1837 to December 1839. It seems so straightforward on the map. With rain threatening the sky is overcast, a sludgy grey, yet nothing will cast a pall over this day.

It began striding the streets of London’s Monopoly board. Look at me in the bright red at Trafalgar Square and Fleet Street, a saunter along canary yellow’s Piccadilly, turning slowly into the emerald green spaces of Bond, Oxford, and Regent Streets before hitting the big monied royal blue of Park Lane and Mayfair. I was so excited I could have passed Go, collected my £200 reward, and happily gone home. But no, there is still a Georgian terrace house to locate. Not even time to sit and wait for a nightingale to sing in Berkley Square.

And then you notice the streets have changed. You are walking narrow cobblestoned laneways. People brush by hugging the walls as gusts of wind pick up. No street signs but look up to the eaves a plaque in Ye Olde English alerts you are entering Dickens territory, Gutter Lane, Great Queen Street, Grey’s Inn Lane, Mutton Hill, Den on Feld Lane, Hockley-in-the-Hole. When you are lost deep within the maze, when you swear you just had your pocket rifled by Oliver Twist and the Artful Dodger, handed a newspaper from Samuel Pickwick, nodded to Pip and Estella, a wink from Old Mrs Wardle, tipped your hat to Nickolas Nickleby, side stepped Magwitch, then hear yourself call “this is bedlam”, you know you must almost be there.

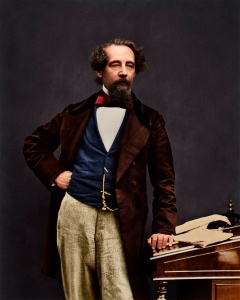

An inveterate observer of life, Dickens walked London seeking inspiration from the sights, smells, soaking up the atmosphere, feeding his imagination on the people he saw and spoke with. He described these experiences as “a magic lantern lighting the toil and labour of writing day after day.” Today, there are many places where the lantern still glows. A quick compendium of statistics from a select number of Dickens’s eminent novels reveal the following number of references to London: Pickwick Papers 101 locations, David Copperfield 79 locations, Oliver Twist 74 locations, Great Expectations 50 locations. Someone has taken a considerable amount of ye olde tyme totting them up.

An inveterate observer of life, Dickens walked London seeking inspiration from the sights, smells, soaking up the atmosphere, feeding his imagination on the people he saw and spoke with. He described these experiences as “a magic lantern lighting the toil and labour of writing day after day.” Today, there are many places where the lantern still glows. A quick compendium of statistics from a select number of Dickens’s eminent novels reveal the following number of references to London: Pickwick Papers 101 locations, David Copperfield 79 locations, Oliver Twist 74 locations, Great Expectations 50 locations. Someone has taken a considerable amount of ye olde tyme totting them up.

The row of three storey plus attic plus basement Georgian terraces in Doughty Street sit in quiet tree-lined simplicity creating an elegant, unadorned stateliness. Terrace 48-49 has a bold high gloss duck egg blue entrance door; a black gloss door knocker and cast-iron picket fence the only contrasting detail. A tasteful sign affixed to the small front fence reads: Charles Dickens Museum, London. Not hard to miss at all.

In his late twenties with wife Catherine and a growing family, Dickens was on the lookout for a grander house that suited his new status. He and Catherine settled on this genteel terrace for the substantial rental price of £80 a year with a three-year lease. Although Dickens only resided here for two and a half years, his literary output was prodigious: completing The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, wrote the whole of Nicholas Nickleby and worked on Barnaby Rudge. In addition, he also wrote four plays and oversaw the productions, and took over as editor of the literary magazine Bentley’s Miscellany, mostly in his study on the first floor, at the back of the house overlooking the garden.

The weather fulfilled its promise of rain, stepping inside Dickens’s house provided welcome relief. The mood indoors complimented by heavy rain pelting on the windows. First impressions, eerie, and small. Granted I come from the expansive land down under and at 188 centimetres tall I don’t fit well in confined spaces. Drawn like a magnet to the exhibits I stepped as lightly and cautiously as possible. The wooden desk and chair at which he sat and brought his stories to light, pens, paper, ink pots, tools of his craft laid teasingly within reach; atmosphere so thick you could swear he was present breathing down your neck.

Dickens was fascinated by the occult. Although he conducted a running battle with spiritualists over exposés of fake mediums and seances he did believe in mesmerism convinced he could heal others by putting them into a hypnotic trance. And it was in this state I turned a corner on the first-floor landing coming face-to-face with his ghost. In one startled yelp I delivered all the ghosts, past, present and future, to a silent museum attendant standing perfectly immobile in the doorway of his sitting room.

Dickens was fascinated by the occult. Although he conducted a running battle with spiritualists over exposés of fake mediums and seances he did believe in mesmerism convinced he could heal others by putting them into a hypnotic trance. And it was in this state I turned a corner on the first-floor landing coming face-to-face with his ghost. In one startled yelp I delivered all the ghosts, past, present and future, to a silent museum attendant standing perfectly immobile in the doorway of his sitting room.

Strangely, or maybe not under the circumstances, I exclaimed “What the dickens?” After which I was treated to a literary insight from the attendant who had regained her composure long before my pulse returned to normal. This expression has nothing to do with the man whose home I was in, it’s simply a euphemism for “what the devil!” Fact is, the expression was common 200 years before Charles Dickens was born, having been used by Mistress Page in Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor (Act II, scene 2): “I cannot tell what the dickens his name is.”

Leaving his Georgian terrace wiser, getting wetter as the rain had not abated I figured the fame of Charles Dickens probably helped keep the idiom in circulation. My day was richer than I could have imagined. What the Dickens would we do without him?