Dreamers

Regional Victoria

Mid 1950s

He wore striped pajamas. Horizontal pale blue and white, a faint red edging the blue. Flannelette. Drawstring. He wore them summer and winter. And slippers. Genuine leather. Soft tan. The heels staved in after years of impatiently shoving his feet into them. That’s what I remember about Uncle Perce. People in town say there wasn’t much worthwhile remembering him for. Nothing much happened here. Nothing much was expected to happen here. He and Aunty Kath hardly went outside the front gate.

He wore striped pajamas. Horizontal pale blue and white, a faint red edging the blue. Flannelette. Drawstring. He wore them summer and winter. And slippers. Genuine leather. Soft tan. The heels staved in after years of impatiently shoving his feet into them. That’s what I remember about Uncle Perce. People in town say there wasn’t much worthwhile remembering him for. Nothing much happened here. Nothing much was expected to happen here. He and Aunty Kath hardly went outside the front gate.

They had nine other nephews and nieces from which to choose but I was their favourite. Aunty Kath always made pink jelly lamingtons when I visited. I knew she hated my cousin Lennie because he yelled “not fritz again” and tossed it over his head. Aunty Kath pushed his face into the mashed potato and blistered his nose. Mum lowered her voice when talking about Aunty Kath how she “couldn’t have children of her own even though she prays a lot. It was probably not God’s fault but poor light-headed Uncle Perce’s. God knows since he came back from the war he’s never been able to hold down a job. It’s a tragedy.” When they lost the farm and moved into town Mum said, “Uncle Perce is a very unsettled soldier settler.” I didn’t care. I loved him.

Saturday mornings I’d jump on my Malvern Star, pedal up the street to the Co-op and pick up their groceries. Uncle Perce used a metal rod he bent himself to fix a billy cart from my bike to carry everything. He said, “now when you go to the pub tell Spider you’ll have a carton of du Mauriers and one of Craven A and a dozen Coopers Ale. Tell him to stick em in the boot mate.” I never knew what was funny, but Spider laughed and said, “Jeez that Perce’s a bloody wag.”

My bike made a great noise. Uncle Perce pegged one of his Craven A packets to the wheel brace that clacked on the spokes. The faster I rode the louder the noise. Me and Uncle Perce laughed because it frightened people. Uncle Perce and Aunty Kath would sit on the verandah waiting for me. As soon as Uncle Perce heard me coming he’d run to the fence, climb on the pickets, pretend he was looking through binoculars and call me in like when we listened to the races.

“Here he comes heading into the home straight. Half a furlong left to race. Young Timothy Prescott is leading by a mile. Wait, there’s someone coming up on the outside. Jesus, Mary and Joseph it’s that bloody mongrel Tojo. C’mon Sport, pedal harder. Harder, they’re gonna catch you.”

I knew the Japs were not there, but Uncle Perce was very convincing. The harder I pedaled the louder the spokes clacked, and the louder Uncle Perce would shout, “they’re gonna catch you Sport, they’re gonna catch you.” I loved that noise. Uncle Perce said it sounded like a motor bike. Sometimes I pedaled so hard I could get through three Craven A packets a week. Uncle Perce said that pretty soon everyone who has a bike will copy us, so we took it off. I overheard Dad on the phone talking to Aunty Kath, “I can hardly show my face at the RSL. Bloody Perce is making a fool of the family. It’s high time he grew up and stopped being such a bloody idiot. Remember Kath, we may not be the most liked family in town but by Christ we’re the most respected.” I think it was Dad’s fault Uncle Perce and me stopped that trick. But we had others.

Me and Uncle Perce made things from stuff he had on the back verandah. Jars of rusty nails, bits of pipe, pieces of canvas, axes, picks, shovels, lengths of string and rope, coils of wire, small tobacco tins full of useless coins and notes with names like Crete, Egypt, and Greece on them, big tins of paint, curled and clagged brushes in jars of turps, brown, blue and violet coloured bottles some with caps some stoppered with corks, bits and brace, drills, screwdrivers, chisels, planes, and hammers all with well worn wooden handles, spirit levels, clamps, tins with rusted lids that had a skull and crossbones on them, rusty rabbit traps and hand shears, papers, lots of papers bundled up and tied with bind-a-twine, hubcaps, a crank handle, bike tyres, lengths and widths of wood, bits of broken chairs tied to the rafters, suitcases and cardboard boxes, a flower patterned dinner set in wrapping paper being kept for best. We made things then nailed them to the front fence and verandah posts. It looked really good. People from across the road didn’t like it much and yelled at us. Uncle Perce and me took no notice. I asked Aunty Kath what Uncle Perce was going to do with all that stuff on the back verandah. She said, “he is always going to do this, going to do that. He’s always going to do something but never gets around to it”. She calls the back-verandah Uncle Perce’s Kingdom of Gunnardoo.

Even though they had a big house they lived in the front room. All the other rooms had the blinds drawn and doors closed. I asked Mum what was in the other rooms and she said, “Dreams, promises, and memories.” I snuck in one day, but they were all empty. Aunty Kath cooked in the kitchen then ran the meals to the front room. We sat by the fireplace, ate, and listened to the wireless. Even the fridge was in the front, mostly full of Coopers Ale. I loved the clink click sound the bottles made when the door opened and closed. Also the fizz when Uncle Perce removed the cap and froth bubbled down the chilled bottle. Afterwards I took the empties outside and stacked them. I could get sixpence a dozen from Hubby Bates the bottle-o. Uncle Perce taught me the gentlemanly art of pouring beer with a proper head. And not in a glass. I got to use Aunty Kath’s anodised cups that tucked into each other in a leather pouch zippered around the top. “Listen to the beer talk Sport. Tilt it a bit, start pouring. Gently now. Hear the sound change? Don’t look at it, it’ll tell you when. Straighten it up, gently now, listen, listen, don’t look. Almost. Hear it? There.” It took a while but gradually I began to hear the beer talk. I became very good at the gentlemanly art. On special occasions I was allowed to light Aunty Kath’s du Mauriers using the six-shooter table lighter. And have a puff. Uncle Perce said, “I’ll teach you to do the draw back when you’re a bit older.” I was in no hurry. The smell of shellite from the lighter made me feel sick.

All I had to say was “tell me a story Uncle Perce” and the wireless would be turned off. For hours I’d be taken into his imagination. He used different voices to act out all the parts. Sometimes creeping other times leaping over the beds and chairs using cushions and blankets to change his shape. What I loved best was when he popped his two front teeth out the side of his mouth and made rabbit noises. No matter how hard I tried I couldn’t get even one of my teeth to do it. Uncle Perce was full of magic like that.

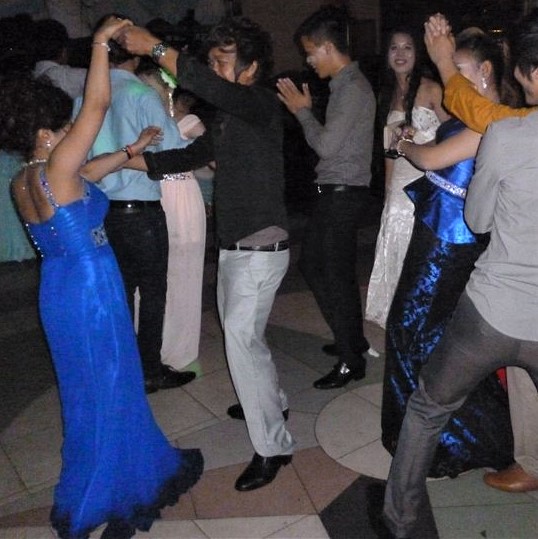

Then it was my turn to sing. Aunty Kath said I was better than Vic Damone and should be on the wireless. I’d stand on the hearth beginning with her favourite, How Much Is That Doggie in The Window. She and Uncle Perce joined in doing the “woof woof” bits. I’d finish with I’ll Take You Home Again Kathleen. Uncle Perce pushed aside the chairs and tables. He’d bend in the middle and say, “may I have the pleasure darlin’?” She’d say, “always.” He’d scoop her into his arms and dance her around in circles. As they one-two-three, one-two-three’d sometimes they had tears in their eyes. Mum and Dad never touched like this. Sometimes I felt embarrassed at the sight of the nightie and pajamas so close together. I suspected it was the rude thing Mum warned me about. Often, I couldn’t finish the song. I’d end up laughing because Uncle Perce’s diddle would pop out the front of his pajama pants.

Some days I’d read the paper out loud for him. Using my best voice I’d put everything I had into it. We’d talk for ages about what was happening in the world. The best day was when Sputnik went into space. That night I snuck out and rode up to Uncle Perce’s. We sat outside in our pajamas with Aunty Kath watching the sky. We saw it go past too. Mum and Dad were really cross the next morning and Mum yelled at Aunty Kath on the phone. I wasn’t allowed to see them for a couple of weeks because they were filling my head with stuff and nonsense. Next visit Uncle Perce found a tin of silver frost in the Kingdom of Gunnardoo and painted my Malvern Star like the sputnik.

Dad wouldn’t tell me where they took Aunty Kath. Mum said, “Cancer. Too many smokes, too much beer, too many broken dreams.” After that, Uncle Perce sat in the front room in silence. He never turned the light on at night. The wireless was off and stayed off. The fire went out and stayed out. Then I found the front gate open, and Uncle Perce gone.