It’s Just Not Cricket

Seriously, I felt if I don’t leave Australia soon I may never go again. India was made easier by my friend Mahin, finding room at his house in Fort Kochi in the southern province of Kerala.

Seriously, I felt if I don’t leave Australia soon I may never go again. India was made easier by my friend Mahin, finding room at his house in Fort Kochi in the southern province of Kerala.

‘Kochi is your home, you come and go from here,’ welcomed Mahin. ‘Mind, Fort Kochi is beautiful you will love it, and maybe not want to leave.’

I arrived early October, two days before India beat Australia by six wickets in Chennai in an early match of the Cricket World Cup playing for a place in the final at the Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad on November 19. Passions run high where cricket is life to the population of India. The current population being 1,442,195,981. I am not a cricket fan; I mention this only because it bookends my Indian odyssey.

Mahin is correct, in Kochi it’s easy to fall in love, especially with the avenues of Rain Trees many over 300 years old. Bustling with life, creativity, art, music, and cuisine, the streets are alive, noisy, exciting and joyful. Walking this enclave of mixed cultures every available field is packed with kids playing cricket, as many as twelve full games run alongside, and among each other. The sound is infectious. I am fronted by a handful of boisterous boys demanding to know where I am from.

‘From the country that has the best cricket team in the world,’ I answer, knowing full-well it was a risky gambit. I got what I asked for.

‘India? You are not from India.’ Voices shouting, bodies jumping in indignation. ‘We are the best so, where are you from?’ they persist.

‘Australia,’ I managed before they hounded me down.

‘We beat you,’ they screamed delightedly. ‘By six wickets we beat you.’

Laughing, cheering, jeering, ‘Australia won’t win the world cup, we will win, you see.’ In seconds they dispersed, running back onto their fields of play.

This conversation played out almost every day wherever I went across India.

Mumbai was my first destination outside my Kochi home. I talked myself into nervousness, convinced I was not up for it. A city of 25 million is the entire population of Australia in one place. Unfathomable to me. Luck was on my side as along with the flight I also managed to include a taxi from the airport to Elphinstone Hotel. How the driver found me, also unfathomable. Seventy-five minutes later, easing the cab out of the crushing traffic to the side of the road he stopped, and pointed.

I had booked myself into a gothic horror. Mortified by what I saw I refused to get out, certain I would not survive the night. A young man grabbed my suitcase, I wrestled him 25 metres down the street in traffic, through what was certainly a heavy iron-barred prison door, to find at the top of the stairs he was the hotel porter sent to welcome me.

Falling through the swing doors with “I’m not up for this shi…” on the tip of my tongue before realising I am in air-conditioned surroundings, ushered to a comfy chair, seated and promised, “a pot of tea is on the way,” before the raging beast inside was soothed, calmed, being addressed quietly by a fine gentleman in gold trimmed olive livery, the Hotel Manager of Elphinstone Hotel, in downtown Mumbai. I damn near cried.

Then came in quick succession shame, remorse, embarrassment, a touch of regret, a modicum of relief, before realisation this is exactly what I needed – to be confronted, turned upside down, thrown off-kilter. I must adapt or run home like a big sooky-la-la and lock myself away from the world, which I won’t do because this is what I came for. I am elated, this is exactly what I wanted after years in the security, and comfort of my home.

Later in northern India, I arrived in time to experience Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, the spiritual victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance. I have been invited to see fireworks, but first dinner.

The red-hot flash of angry black eyes is unmistakeable. Mother in tangerine, to daughter-in-law in cadmium. Not even the sudden readjustment of the cadmium yellow sari, or from the headwear of the tangerine sari could cover it quickly enough. Stationed two paces behind, is the gleam of delight in the downcast eyes of the housemaid.

Only twenty minutes earlier I stood at the front door of a very fine house in a well-to-do area of Jaipur, in the Rajasthan province of northern India. The occasion, a family feast to celebrate Diwali festival. I was warmly welcomed inside by the young woman in an opulent cadmium sari, gold bangles jingled joyfully on both wrists. Her two young children ushered out of sight by the housemaid. She apologised her husband was absent, work held him over in London another month. It was just her, and her mother-in-law.

As dinner progressed, the young mother in cadmium withered before my eyes under reproachful glares, averted glances, ignored, and frozen out of conversation by the older woman glowing in tangerine. Whose armful of bangles, by the way, jangled loudly.

As dinner progressed, the young mother in cadmium withered before my eyes under reproachful glares, averted glances, ignored, and frozen out of conversation by the older woman glowing in tangerine. Whose armful of bangles, by the way, jangled loudly.

The eyes sadden in the face of the university educated and qualified doctor in cadmium yellow, forbidden now to practice. She relinquished her career the moment of her marriage, when moved from her family home into her husband’s. Her first duty now is to manage the home she lives in, under the watchful, and reproachful eyes of her husband’s mother. The woman in tangerine crows about her outside the home. Boastfully about her son and two grandchildren, how wonderfully his wife is fulfilling her promise. Behind closed doors another story is being lived.

Australian society understands domestic abuse as an act between a victim and her partner, as intimate partner violence. The situation I witnessed is domestic abuse at the hands of the mother-in-law, not snappy banter, playful fun, it is demeaning, deliberate, and on-going coercive control.

The gold bangles have fallen silent on the wrists of the cadmium sari. The unbroken chatter of bangles ring on the arms of the tangerine sari. While from the housemaid, the subservient rattle of acquiescence subtly assures her position remains secure in the household.

Traditionally bangles, a symbol of a woman’s marital status, are believed to bring good fortune, and prosperity to the husband and the family. The sound of bangles is considered auspicious, believed to attract positive energy and ward off evil spirits. Except when evil shares the same table.

Returning to Kochi and my love affair with the Rain Trees, to gaze fondly one last time before returning home. Pulling me up short, and out of reverie is the shouted demand of a schoolboy in his snappy school uniform.

‘Where are you from?’ he barks. Crossing the road, he planted himself toe to toe directly in front of me. What he lacked in height he made up for in chutzpah.

‘I’ll tell you this much sport,’ I raised myself to my fullest. ‘Tonight, I take home with me a huge gold cricket trophy.’

‘I’ll tell you this much sport,’ I raised myself to my fullest. ‘Tonight, I take home with me a huge gold cricket trophy.’

‘Aussie!’ he shouted, wagging a reproachful finger in the air. “Bloody India they played bad cricket. You win by six wickets. It’s all Modi’s fault.’

I didn’t have to ask him to go on, his passion riled he was only warming up.

‘Modi changed the stadium to his name, it made our players feel bad, like they play for him, not India. That’s just not cricket. Good on Australia. I am glad you won; I hate Modi. I am going to assassinate Modi.’

‘I admire a lad with ambition,’ I replied. ‘How old are you sport, maybe twelve? You want to spend the rest of your life in prison? That’s a big price to pay.’

He stopped and thought a moment. I could see he was weighing up options.

‘I will write him a letter,’ he said with resolve. A breath later adding, ‘And tell him – I’m going to assassinate you Modi.’

‘Just a word of advice,’ I offer. ‘Don’t sign it.’

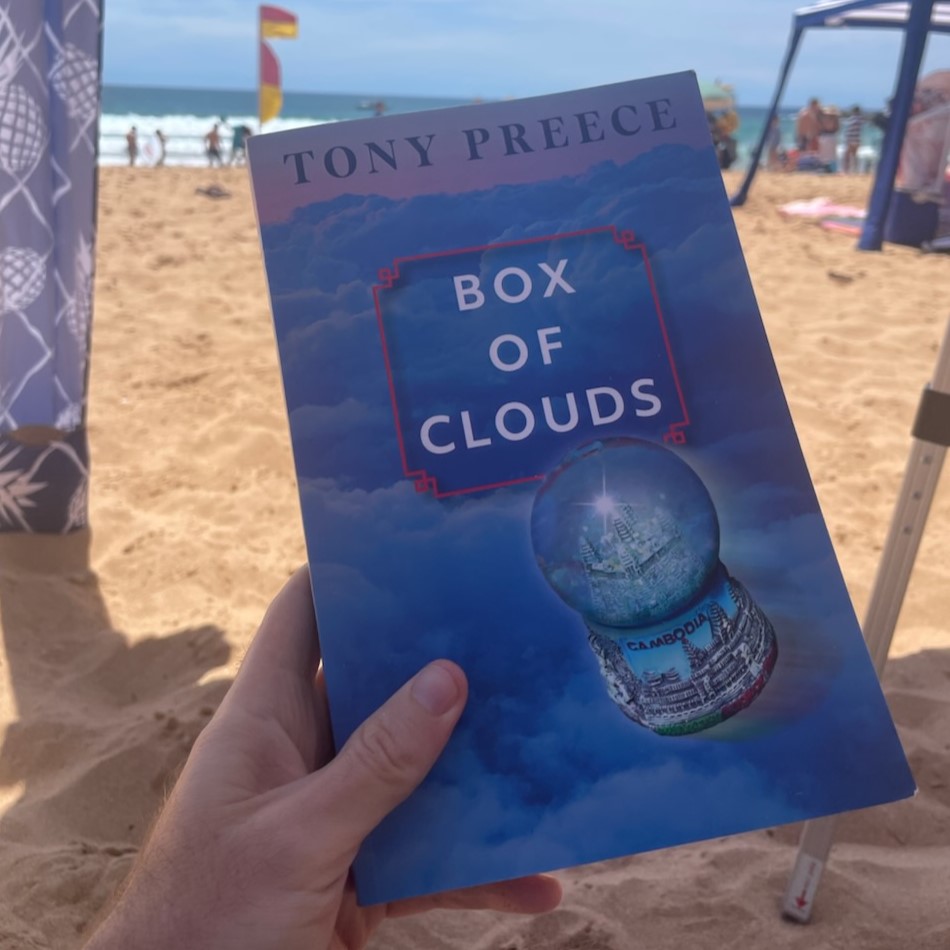

If you’d like to comment, leave a message, join The Godless Traveller’s Glittering Email List: https://thegodlesstraveller.com/contact/